The Key To Learning Is Unlearning

My parents took our family on a trip to Maine to ski when I was in my early teens. The mountains there are really big, and I was not ready to ski those slopes. I was a bit scared to do anything but put my skis in a wedge (pizza style) and slow-mo my way down the mountain.

My dad (not the best skier either) told me a story about his first time skiing. He was a city boy growing up who didn’t get the opportunity to learn how to ski until he was leading a group of teenagers on a trip to a local mountain. It took him a while to tie the skis to his boots (this was before the fancy click-in skis we have today) and he headed to the lift to get carried up to the top.

He explained how he watched the ski lift pass a couple of times before he got the hang of how to catch it at the right moment (if you’ve ever been skiing this is a critical skill!). Then as he stepped onto the lift platform, BOOM, it hit his leg and he half-slid onto the seat as it began to rise up in the sky.

Unaware of the bar to pull over your head, my dad grabbed the side of the lift-chair, holding on for dear life. He looked around. No one was noticing him struggling. As he regained composure and sat upright in the chair he realized that the tie on his left ski had been undone and it was hanging by a thread on his boot. Then, he looked ahead and saw where he would have to get off the lift. Instantly thoughts began to fill his head. What if I came off the lift and broke my ankle? What if I fell and slid down unable to control where I landed? He scanned the area and came up with a plan: He was going to jump off the chair onto one of the big metal poles holding up the lift!

As he began to rock back and forth in his chair, people below took notice. What was that man doing in the chair? Why was he rocking so hard without his bar placed in front? What was he going to do???

His group of teenagers also saw what was happening, but it was too late. My dad timed the rocking to a point where he jumped off the chair and onto a big pole. The crowd gasped. He slid down the pole, skis still on his feet, until he landed on the snow below. Immediately, people rushed to his rescue, but as they got close all they could hear was him laughing…at that moment, he had finally realized how ridiculous he must have looked jumping off the ski chairlift!

LEARNING AND UNLEARNING

The story made me feel better about my awkwardness as a beginner skier, and it still speaks to me years later. When we learn something new we often have a pretty picture in our head of what that is going to look like. Yet, in reality, it often looks much different.

Learning something new can be exciting and exhilarating but it can also be tiring and frustrating. In my dad’s case, it can also be embarrassing. But I don’t believe that is just limited to his skiing story.

How many times have you personally not given your best (100%) effort to learn and try something new because you’d look like a fool and could potentially embarrass yourself?

DON’T FEAR FAILURE SO MUCH THAT YOU REFUSE TO TRY NEW THINGS. THE SADDEST SUMMARY OF A LIFE CONTAINS THREE DESCRIPTIONS: COULD HAVE, MIGHT HAVE, AND SHOULD HAVE. – LOUIS E. BOONE

I’d like to call myself a risk-taker, but guess what? I spent five years in a band around musicians who could play multiple instruments and I never learned how to play guitar, or the drums, or the piano. I spent countless hours writing lyrics, but was too scared to really spend time learning an instrument. Want to know why? I had bad experiences. Whether it was the trumpet in fifth grade, or the piano at my house, I categorized myself as someone who could never learn an instrument.

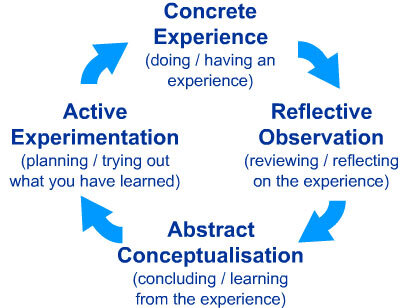

I didn’t follow through with the entire learning process, as described in this diagram of Kolb’s Learning Cycle:

I would play the guitar (concrete experience), have little to no success (reflective observation), and then conclude I was bad at playing the guitar and would never get any better (abstract conceptualization). So, active experimentation never truly happened because I’d already pegged myself at a skill level…

Does this sound like you at all? Does it sound like any students in your class? Does it sound like any of your children?

It’s why learning in isolation is often so difficult. We have little-to-no feedback to rely on except for how we perceive the process. It’s also why teachers, mentors, and guides are so vital to learning. Let’s look at the diagram again, but this time with a mentor available and willing to help guide you along the way:

Learning changes with a teacher/guide/mentor. Teachers inspire, challenge, and help push learners to active experimentation, even when we as learners aren’t sure about our perceived skills.

I see this all the time with my own kids. Whether they are learning to ride a bike, talk for the first time, or understand the basics of math, feedback is critical to their learning process.

But what does it look like when you’ve hit success in all of these areas and then are suddenly told you need to change and learn something new?

What if you’ve stopped the active experimentation piece of the cycle because for years and years the feedback you received is that you’ve mastered this skill already?

And what if that “years and years” part has changed to “months and months” and “days and days” in the past few decades? What if every time you learned something new and thought you had a solid understanding it changed? What if this happened repeatedly in all different situations in your life?

Sounds frustrating right?!

But that’s what is happening right now. It’s why “learning” has changed, and how “unlearning” is the key to a radical revolution in the present (and future) of learning.

UNLEARNING THROUGHOUT HISTORY…

I remember coming back home from an elementary school lesson and telling my parents that people actually thought the world was flat, and they actually thought the earth was the center of the solar system.

How crazy of them!?

And yet, each generation has had these beliefs that were later proven to be completely wrong (or misguided) and indefensible in light of new information or scientific discoveries.

Let’s take the earth as the center of the universe example. Europeans were basically using the old Greek beliefs of the solar system. Some people questioned these beliefs, but they played perfectly into the religion, culture, and science of the time. There were problems with the theory, but if no one actually believes it is a theory (and believes it to be pure truth) then it is extremely difficult to disprove.

Copernicus comes around and just drops a knowledge bomb on the entire world (while on his deathbed) when he publishes a book supporting his “sun as the center of the solar system theory” (let’s finally call it heliocentric) in 1543. Well, no one believes him. They call it heresy. And most people go about their business the same as before.

It took over 100 years for new physics to be devised to support heliocentric astronomy. The works of Galileo and Johannes Kepler in physics and astronomy were needed to gain public support around this theory.

By the time 1650 rolled around most astronomers (thanks to Galileo’s efforts) believed the science supported the heliocentric view on the world, and helped persuade the public on the validity of this theory.

We can look at this from two different learning lenses.

First, most of this learning was done out of interest, not necessarily necessity. Explorers were crossing the Atlantic using the old view of astronomy. So most people thought they were smart enough to go anywhere and do anything with their current belief system about the stars. We’ve seen other seismic shifts in human thinking come out of necessity, but this (along with many scientific discoveries) came from the human desire to be curious and challenge through interest.

Second, look how long it took for a theory that was completely justifiable to actually be accepted by the general public. Over 100 years!

Imagine if it had taken that long for our world to agree on Einstein’s general theory of relativity. It took all of five years for Einstein to propose the theory and for Arthur Eddington to prove its validity during a solar eclipse in 1919.

So, as humans, we’ve always had to unlearn. Whether that is my young son touching a cold stovetop one day and believing it is ok to touch; and then hitting it again the next day when it is on and hot (this happened recently in my house) and realizing it is not ok to touch. Or it may be scientific discoveries or theories that we accept and unlearn a past practice or belief.

We’ve always improved through unlearning and relearning, although the unlearning used to have a longer curve to it. In fact, we’ve seen social unlearning (think cigarette smoking) struggle to happen fast compared to pure scientific unlearning.

So what does this mean to us as leaders and teachers and learners?

Well, it means we have to unlearn and relearn at a much more frequent pace than generations before us, and this pace will increase in the coming years and generations.

When you are at work, or at home, and think that you cannot simply handle one more change…sorry…the changes won’t stop, they are going to keep coming in waves, and there’s not much you (or I) or anyone can do about it.

PACE OF EXPONENTIAL CHANGE

One of the facts from the Did You Know; Shift Happens video that struck me as crazy was the pace of exponential change.

BUCKMINSTER FULLER CREATED THE “KNOWLEDGE DOUBLING CURVE”; HE NOTICED THAT UNTIL 1900 HUMAN KNOWLEDGE DOUBLED APPROXIMATELY EVERY CENTURY. BY THE END OF WORLD WAR II KNOWLEDGE WAS DOUBLING EVERY 25 YEARS. TODAY THINGS ARE NOT AS SIMPLE AS DIFFERENT TYPES OF KNOWLEDGE HAVE DIFFERENT RATES OF GROWTH. FOR EXAMPLE, NANOTECHNOLOGY KNOWLEDGE IS DOUBLING EVERY TWO YEARS AND CLINICAL KNOWLEDGE EVERY 18 MONTHS. BUT ON AVERAGE HUMAN KNOWLEDGE IS DOUBLING EVERY 13 MONTHS. ACCORDING TO IBM, THE BUILD OUT OF THE “INTERNET OF THINGS” WILL LEAD TO THE DOUBLING OF KNOWLEDGE EVERY 12 HOURS.

And not only is our knowledge doubling at a rapid rate, but also the amount of data is growing exponentially. Look at this chart depicting how much data we are currently dealing with:

Crazy right? And a myriad of other growth factors has many researchers, futurists, and scientists believing we are on an exponential upward swing of progress. This progress can mean many things, but let’s not debate that right now. Let’s just look at the information and acknowledge the tremendous amount of growth we have seen and most likely will see in the coming years and decades.

Image: This is how Tim Urban of Waitbutwhy.com depicts the growth trajectory.

If the research, observations, and data are even close to being correct in their understanding and predictions, then we are going to have to get ready to do a whole lot more unlearning in the very near future (like right now).

It also means that our ideas of what learning looks like are going to have to change. And it starts with accepting and embracing the unlearning cycle.

THE UNLEARNING CYCLE

When looking at why we learn it can be boiled down usually to two reasons: Interest and necessity (both tied to attention). These two reasons take various different forms (survival is a form or necessity) and can be interchanged with other terms (curiosity is similar to interest), but if you think about your life and what you have learned it usually comes down to things you had to learn and things you wanted to learn.

The part of all this that is mind-boggling to me is that for centuries and centuries the necessary part of learning slowed down as you aged. The world wasn’t changing that rapidly, and as you became an adult there wasn’t much forcing you to learn (although I’d have to say my kids have forced me to relearn a lot). Sure there were always new learning experiences to be had, but the unlearning didn’t happen like it does today.

My dad (the one who can’t ski) has had to unlearn and relearn seven different cell phones in the past 12 years! He’s had to unlearn modes of communication and relearn how to communicate with his family and friends. It seems like each holiday season he’s getting a new technology in his hands that makes him unlearn what he learned the previous season. His life at almost 70 years old is filled with monthly and daily unlearning occurrences, and he is relearning at a faster and faster pace each year.

The real kicker is that most of these unlearning and relearning experiences are coming out of necessity, not out of interest.

To better understand this process, I want you to watch a video that I share almost every time I speak around the country. It’s one of my favorite videos because it “shows” instead of “tells” about this process (Also, Destin the host of SmarterEveryDay is both smart and funny. His Youtube channel is amazing).

It’s about a guy, a backward bicycle, and an unlearning situation that describes the exact feeling that my dad (and millions of people around the world) has when he has to go through the unlearning cycle:

In the video (did you watch it yet?), Destin makes a very important distinction:

“TRUTH IS TRUTH, NO MATTER WHAT I THINK ABOUT IT. SO BE VERY CAREFUL HOW YOU INTERPRET THINGS, BECAUSE YOU’RE LOOKING AT THE WORLD WITH A BIAS WHETHER YOU THINK YOU ARE OR NOT.” — DESTIN AT SMARTEREVERYDAY

We are looking at the world through a bias. Our bias includes our experiences, our upbringing, and our environment. We have many biases around the ideas of learning.

The truth is that when you look at our learning from a first-principles perspective, a lot has changed. A lot is going to change. And learning is no longer a linear process. It is one where we have to take steps to the side, and steps backward, in order to relearn and recalibrate our biases, beliefs, and understanding of the world and what will work.

What we know though is that many people believe that change is bad, very bad:

It’s not just that people fear change, though they undoubtedly do. It’s also that they genuinely believe (often on an unconscious level) that when you’ve been doing something a particular way for some time, it must be a good way to do things. And the longer you’ve been doing it that way, the better it is.

So change isn’t simply about embracing something unknown — it’s about giving up something old (and therefore good) for something new (and therefore not good).

A November 2010 study shows that people have a very reliable and tangible preference for things that have been around longer. In one study, students preferred the course requirement described as the status quo over a new version (regardless of whether the new version meant more or less coursework), and liked it even more when it had been around for 100 years rather than only 10 years.

How do you view change? Do you accept that the world is changing, or continue along with the same biases towards learning and education?

Hopefully your answer to that question now is, “YES, I get it AJ! The world is changing at a rapid pace and I have to embrace this idea of unlearning and relearning!”

So, maybe you don’t need to yell that from the mountaintops But, if you are a teacher, leader, or parent it’s important to acknowledge that we are going to have to learn, unlearn, and relearn as much (or maybe even more) than our students and children do.

Sam Dyson, in an awesome article for EdWeek puts it this way:

Deeper learning requires connecting old and new knowledge in initially unfamiliar ways. While knowledge is an indicator of what information we have access to, understanding indicates what connections we are able to make between one bit of knowledge and another. According to Understanding by Design by Wiggins and McTighe, “Misunderstanding is not ignorance, therefore. It is the mapping of a working idea in a plausible but incorrect way in a new situation.”

He views unlearning like this:

While Jal Mehta looks at unlearning and relearning as a longer process where you learn more through the process of unlearning:

And finally, let’s look at the Unlearning Curve Framework by Jack Uldrich:

Did you notice the similarities in each of the pictures?

Unlearning has to be followed by relearning.

Here are the steps that we take:

1. An Interest or Necessity (with excitement or urgency) leads to Learning

2. An Interest or Necessity (with resistance and/or urgency) leads to Unlearning

3. An Interest or Necessity (with excitement or urgency) leads us to Relearn

My question then is: Do we allow for this process in our learning environments? And do we promote this process in our schools?

BRING IT BACK TO THE BASICS

We’ve always been learners, and it is innately human to want to learn. But, what we’ve seen is that we always have been unlearners as well. Unlearning has been as important a process to our growth as any other factor.

The problem is that unlearning is hard. It rails against our biases. It takes our feedback and turns it upside down. It makes successful people fight for things to stay the same. And it makes even the most forward-thinking individuals question whether or not the process is worth it…

The implications for school are even more important. If our exponential change curve has unlearning and relearning happening at a much faster and faster rate, then consider this:

Most curriculum cycles in schools are longer than five years

Many students don’t get a chance to retake assessments or redo work (no unlearning allowed!)

Schools create K-12 scope and sequences for specific content (most of which will be outdated by the time students are in 4th grade)

Students are often encouraged to “pick” a career path and major before they even graduate high school

Countless professions have one or two tests that “certify” individuals without testing their skills or abilities when the world changes (and when their profession changes)

The list can go on and on. We are living in a world of exponential growth that still uses fixed measures.

Education needs to not only look to what the future is going to be in order to better teach and learn; but also look in the mirror to acknowledge the realities of our current learning environments. Let’s celebrate unlearning in our schools and classrooms, and find more ways to make relearning a daily practice that we support and promote.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A.J. Juliani is the author of 8 books about learning, including best-sellers Empower, Launch, and Adaptable. He’s worked at every level of education as a teacher, coach, administrator, and UPenn GSE PLN. A.J. speaks around the world about learning, goals, and innovation.